Cost, Design and Data in Subsea

This article was first published on first published on Linkedin on 12th November 2016.

Traditionally, subsea oil & gas has based its designs on simple engineering theory, because it’s regarded as being more reliable to do it that way. However, now the low oil price is bringing to the fore the view that the cost of constructing and maintaining subsea infrastructure is too high, due to over-design and poor understanding of how structures actually behave in the field. This situation was tolerated in the past when the oil price was higher, because it was regarded as robust and lower risk to over-design pipelines and other subsea infrastructure. Now there is immense pressure to reduce costs, and to keep costs down when the oil price recovers again, while somehow at the same time maintaining the necessary standards of safety and reliability. It will not be possible to achieve this by doing things the old-way. If costs are going to be reduced without increasing risk, then it will be necessary to introduce new innovative technologies, to collaborate, and to move beyond the simple engineering theory that we have relied on in the past, to start using more advanced engineering analysis, and to start looking at our data to see how our designs actually perform.

The oil & gas industry is in crisis. The oil price has been lower for longer. Spending has been cut 20%-30% across the board. There have been large scale job losses in the UK, Norway and the USA. We are being told that the lower level of spending must be sustained when the oil price eventually recovers. At the same time, there can be no compromise on safety and reliability. But is it actually possible to cut costs in subsea without increasing risks?

No, it’s not possible

Many of our colleagues in subsea don’t believe that it is possible to cut costs without increasing risk. There are plenty of stories about subsea projects where spending was reduced, and some type of incident occurred. The implication is always that the untoward incident was a direct consequence of cost cutting, and that it wouldn’t have happened if more money was spent on equipment and hiring additional people, like in the old days when the oil price was higher. Many in the industry still believe that the best way to deal with the downturn is to retrench, wait for the recovery, and then things will proceed as before. After all, that’s what happened after the last downturn, and the one before that.

Yes we can

Meanwhile senior oil company executives are going to conferences and telling everyone that we are going to to learn from each other and embrace innovation. We will make more use of technology and data. There will be more collaboration and standardisation. That’s how we will square the circle and make cost cutting consistent with safety and reliability. However, unless senior management are delivering this same message to their own middle managers (the people who actually execute the work), nothing is going to change any time soon. In the past, the message to middle management has always been “you’re responsible”, and that is the reason why managers in oil & gas are very conservative, risk averse, and wary of change and new technologies.

Beyond the retrenchment and the rhetoric, what is actually technically possible?

The design of a major system could be carried out in a few seconds … and documented automatically

The subsea industry has been aware for some time that most of the analysis part of a pipeline design could be carried out automatically by computer. It is not hard to see why: a pipeline is one of the simplest engineering structures, an extended cylinder, and the engineering analysis is correspondingly simple, based for the most part on basic engineering theory. The quotation above is taken from the book Subsea Pipeline Engineering by Palmer and King, which was first published in 2004. Palmer and King are not tech evangelists, they are distinguished engineers who have contributed to subsea since its pioneering days in the 1970s. The fact that they identified the potential for automating pipeline analysis more than a decade ago is indicative that the idea was already in-the-air even then. Around the same time this book was published, I had the idea of automating pipeline calculations by encapsulating them in a single spreadsheet, but when I described this idea to the management of the company I was working for I was told “interesting, but no-thanks” (I responded “if our competitors do this first, you will want to implement the idea immediately”) . When I tell this story to industry colleagues, they often respond with similar stories of their own about ideas for improving efficiency that were not taken up. The fact is that our rivals did not automate the pipeline calculations, and we didn’t either. The industry had a very good business model based on selling engineering man-hours, and ideas for doing things faster were not consistent with this.

Civil engineers, when designing a bridge, consider the largest loads they can think of, and they apply all those loads at the weakest point, all at the same time, … and then multiply by 10 … but you’ve never seen a concrete bridge taking off from Heathrow airport.

This observation, contrasting the design approaches of the civil and aeronautical branches of engineering, was made by a stress analysis lecturer called Jarlath Mullins to a class of mechanical engineering students in an Irish university around 1988. I have sometimes quoted Jarlath to my subsea colleagues, particularly when they use the phrase “it’s conservative” to justify increasing a load or FoS, or to avoid carrying out further analysis. The reaction to this quotation is rarely appreciative, it usually provokes justifications along the line that “it’s different for subsea”. The next time you hear a colleague saying “it’s conservative” ask yourself this question: is this a necessary prudent approach to reducing risk due to a genuine lack of information, or is it just defensive engineering, or even worse, laziness and ignorance?

Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don’t know which half

Subsea is in a similar situation as the advertising industry a century ago, we are spending too much money on unnecessary subsea interventions because we don’t know when the risk of structural failure is genuine or not. Our assessments of risk are based on very conservative design codes that rely on large factors of safety to ensure reliability. We make too many conservative assumptions, often inconsistent assumptions, and sometimes unacknowledged assumptions, in our attempts to eliminate risk. We could tackle this problem the same way the advertising industry resolved theirs: by using data to understand the problem. Subsea infrastructure are regularly surveyed for integrity management, and these surveys generate large quantities of video, MBES and other data. Apart from compiling integrity check-lists and some basic engineering design checks, this data is not used as much as it could be. The survey data could be used to gain a better understanding of how pipelines and other infrastructure actually behave in the field. Doing this would help subsea move away from its current theory-based engineering approach to a more reality-based engineering approach. The data could enable better quantifications of risk and more justifiable design factors of safety, resulting in significantly lower costs through more efficient designs and fewer unnecessary interventions.

Collaboration and data sharing

There is growing recognition that more value can be gained from data by sharing it, in cases when considerations of privacy, proprietary or confidentiality are not paramount. This has led to an explosion in the quantity of publicly available data, including metocean and bathymetric data directly relevant to subsea. Data licences similar to open source software licences have been developed to facilitate data sharing. The UK government recently issued the 3rd version of its Open Government Licence to protect data issued under Crown Copyright.

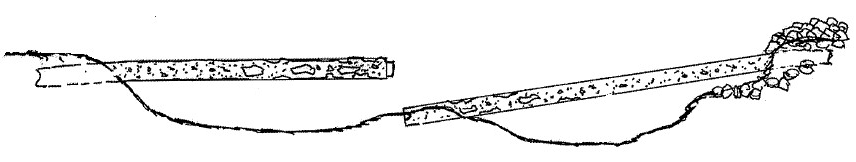

In the oil & gas industry, a narrow, proprietorial, need-to-know approach to data sharing still prevails. This approach may be justified for seismic data which has monetary value and is share-price sensitive, but is it justified for subsea data? You can’t sell your pipeline survey data to another oil company, and ROV video is unlikely to a greater impact on company share value than Google Street View. I am not suggesting that we put ROV survey data on YouTube, I am saying that we will extract more value from subsea data if it is distributed more widely among interested parties, because the more data we have, the more confidence we will have in the risk quantifications it yields. When your engineering contractor tells you that a 12.5m freespan recently discovered in your 10” pipeline is a VIV risk and it requires a £1 million intervention to be remediated, you might wonder whether the risk is real regardless of what the design code says. After all, there have been more sightings of the abominable snowman than field observations of VIV in subsea pipelines.

If the new-found idea of collaboration in subsea actually means anything more than the normal mutually beneficial cooperation between businesses that would happen anyway, then data sharing should be at the top of the list of areas with potential for real collaboration.

In conclusion

The subsea oil & gas industry can achieve its goal of sustainably lowering costs while still maintaining the highest levels of safety and reliability in subsea infrastructure by doing things differently, in particular by making more use of technology and data, and by collaborating more than we have in the past. We will soon find out if the industry can transform itself, or if it reverts to its old-ways, when the upturn finally arrives…